Rev. George Frederick CROSS & Ada CAMBRIDGE

"Parsonage on the Wannon"

"Holy Trinity" Anglican Church, Coleraine 1865+

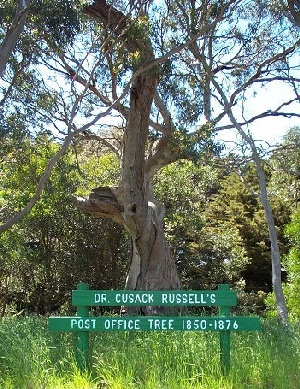

The foundation stone for the Church of the Most Holy Trinity, Coleraine was laid in 1865. The pastor was Dr. F. T. Cusack RUSSELL who resided at the "Parsonage on the Wannon" by the Wannon River, south of Coleraine from 1851 until he left for a trip home to Ireland in 1875. He died on the return voyage from Ireland in 1876 and was buried at sea.

DR. RUSSELL arrived in the Wannon district in 1850 and held the first service in the "Koroite Inn" in Coleraine. At this time the District of Wannon extended from Heywood in the south to the South Australian border and as far north as Chetwynd. It included Heywood, Digby, Merino, Henty, Sandford, Casterton, Chetwynd, Coleraine, Tahara, Balmoral, Hamilton, Branxholme and the surrounding districts. James BONWICK in his book about his 1857 horseback ride through Western Victoria noted:

The Anglican District of Wannon was reorganised late in 1876 with the formation of the parish of Casterton, incorporating Merino and Digby.

In 1853 a building was erected in Coleraine to serve as both a Church and a School. The building was known as the School House and consisted of two storeys. The ground floor was used as both a school and a church.

In 1857, Mr John McDONALD 1819-1885 (father of Major Norman McDONALD 1872-1957) was appointed head teacher and he commenced classes on the 1st July in the downstairs room during the week.

Vestry

The first Vestry or Committee was formed in 1863 and consisted of the following:

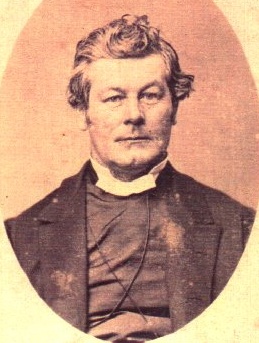

Rev. Dr. Francis Thomas Cusack RUSSELL, BA, LL.D

Rev. George Frederick CROSS & his wife Ada CAMBRIDGE

The Rev. George Frederick CROSS arrived in July 1877 to take up the vacancy created by the death of the Rev. RUSSELL. George CROSS and his wife Ada CAMBRIDGE (Poet & Author) took up residence in the "Parsonage on the Wannon".

1903: "Thirty Years In Australia" - Ada Cambridge

Ada CAMBRIDGE wrote her book "Thirty Years in Australia" in which she included a number of observations on the time they spent at the "Parsonage on the Wannon" from 1877-1884.

She writes on her husband's appointment to Coleraine in 1877 as the replacement vicar for the Rev. F. T. Cusack RUSSELL.

Here, at any rate there was no fault to find with the parsonage house, unless one objected to its lonely situation - which we did not. As a parsonage house it was unique in Victoria, and I believe in Australia. The wayfaring stranger might have taken it for another station homestead, on a smaller scale than most; as in fact, he frequently did, in the person of the professional sundowner... Ada CAMBRIDGE writes on their move into the "Parsonage on the Wannon" in January 1878 after living with one of the local "Squatter Mansions" from July 1877. Rev. Cusack RUSSELL and his wife had lived in from 1851 until 1875 when they left for their overseas trip.

The first incumbent - a D.D. [Rev. F. T. Cusack RUSSELL], eminent in the Church and in the history of the Western District, a pioneer himself, whose name is now perpetuated in a Trinity College scholarship - began his long ministry as a missionary at large. He saw all the changes that turned the fertile wilderness into the garden of Victoria, studded with wealthy homesteads and prosperous towns, while sitting, as Dik would say, upon his own valuable part of it, living the same pastoral life as the squatters around him. The reader will remember that the term "squatter", with us, means roughly the landed gentry; in its original sense the word has no meaning now.

In his old age Dr R. went "home" for a holiday, leaving two curates in charge. Shortly before he was expected back, came the news of his death, and, after a sorrowful time of inaction on the part of the mourning parish, G. [Ada CAMBRIDGE's husband, Rev. George Frederick CROSS] was selected to take his place. It was always impressed upon us that it was to take his place, not to fill it, which nobody could do.

For six years we lived as he lived. Then the authorities six miles off decided to put an end to the old regime. Incumbent No. 3 had to be brought into line with other incumbents somehow. His property could not be sold, but apparently (with his consent, I presume) it could be let; for let it was, as soon as we had vacated it. Tenants of a class to suit the house needed more than 100 acres of land with it, so it was let to a farmer, an ex-free selector, whose selection adjoined. He took up his abode in what we called the "old part" - the original house (our kitchens, store-rooms, etc.), to which, according to Bush custom, another and better had been attached, the two being connected by a planked, bark-roofed, trellis walled passage; and he used my drawing-room and our other living-rooms to stack his produce in. And the parson went to live in the town, beside his church - in a corrugated iron house that was run up for him. Ada CAMBRIDGE writes on the location of the "Parsonage on the Wannon".

Ada CAMBRIDGE writes on some of the problems created by the isolated location of the "Parsonage on the Wannon", it being six miles from the township of Coleraine.

Ada CAMBRIDGE writes on the employees who made up the household at the "Parsonage on the Wannon".

The kitchen party were not at all lonely in these wilds. They had friends on the neighbouring stations and farms, with whom they foregathered in their leisure hours; they had many picnics and excursions to the town; they gave a ball every Christmas (which rather scandalised a section of the parish, although the rigid etiquette observed at them might have been copied with advantage in higher circles), and were tendered balls in return. At ordinary times they seemed sufficient for themselves. Sitting in my detached house of an evening, I would hear cheerful sounds from the other building, and, being mysteriously summoned thither, would find the groom, with his concertina, playing reels and jigs for the little ones to dance to, the dancing-mistresses standing by to enjoy the achievements of their pupils and the surprise they had prepared for me... Ada CAMBRIDGE writes on the establishment of a school close to the "Parsonage on the Wannon", its first teacher referred to as "Miss C." and its effects on the household. This is most likely to be the first Tahara Bridge school, but who was the "Miss C."?

She came to us one day in great distress - perplexity, rather, for she was far too sensible to make a fuss. She could not, under the circumstances, live alone in her school quarters, and she tried in vain to find lodgings in the farmers' cottages: they were all far too small and full. What should she do?

She was an extremely nice girl, and, finding, we could solve her difficulty in no other way, we took her in ourselves. Strange to say, the experiment answered admirably. In the servants' house there was a large spare room, which had been Dr. R.'s study. We put a screen across the middle of it, made a bedroom behind and a simple sitting-room in front, and there installed her. She attended to her own little housework, and the servants took her in her meals from the adjacent kitchen - a job to which they had no objection in the world; and she used to sit in her basket chair on their common verandah and pass the time of day with them when so inclined, and adjusted herself to the position generally with perfect taste, just as they did. To us personally she made no difference whatever, except in her services to the children. She paid us the trifle that covered the cost of her board, and as a further return for hospitality took the two older little ones to school with her once a day, taught and specially shepherded them back again. So, by accident we kept faith with the Government after all; and anything like the rapidity and thoroughness with which the drudgery of the three R's was got through in that little school-house I never saw. I used to walk over the paddock of an afternoon to see the process. We made a new track across the paddock with our goings and comings, the home-returning before nursery tea being usually a family procession, led by the baby's perambulator. We were amused one wet winter to find Miss C. and her charges making a bridge of a bullock's carcase that conveniently spanned a muddy rift. They went over it, they said, until the ribs bent too much and threatened to "let them through."... Ada CAMBRIDGE writes on being part-time farmers on their 100 acres at the "Parsonage on the Wannon" from 1877-1884.

Alas! the usual fate of the amateur farmer befell us. Perhaps we were not there long enough. Certainly we had the worst of luck in the matter of the seasons. It was one long series of droughts, punctuated by those floods already alluded to, which came at the wrong time to benefit the grass. The store cattle would not make fat, on which we could make a profit; the precious "water frontage", when it became a rope of sand threaded with water-holes, unfenced one side of the property, allowing the stock to stray at large. The stock, also, by degrees became largely composed of unproductive horses, those happening to be G.'s special weakness and temptation. He had an assortment, continually being added to, for his own riding, and we had two concurrent pairs for the buggy; the groom had one or two for his constant journeys to the post, and there was one for the wood-cart. They were for ever going to be shod, or they met with accidents and had to be replaced. The most valuable that we ever possessed was pricked in the haunch with a point of fencing wire - a wound almost invisible to the naked eye - and died of lockjaw from it.

Finally, we let fifty acres to a real farmer at £1 per acre. He strongly fenced this off, and grew lovely crops of corn on it. And I think that was about all the "increment" we enjoyed.

Here we learned something of what the Bush settlers have to suffer in our frequent years of drought. We had a large underground rain tank, with a pump to it, but there were times when it seemed a perfect sin to wash. Our selector neighbours had only their own zinc tanks and the river - muddy, and fouled by creatures alive and dead; and the nurse and children used to make it an object of their evening walks to carry little cans of water to their friends, to make at least one nice cup of tea with. It was regarded as a handsome present. Hydatids raged over the country-side. Two of our servants (who married each other, and went to live at the schoolhouse by the river, Miss C.'s empty quarters) were crippled with the disease... Ada CAMBRIDGE writes on being close to nature, the bird life (ducks, cranes, swans, native companions, eagle-hawks) and animal life (possums, platypus, water rats, hares, wild cats, yabbies, blackfish) in and around the Wannon River at the "Parsonage on the Wannon" from 1877-1884.

We had all the birds of the country flighting over us in the grey dawns and the golden twilights. The lovely gabble of the cranes and the wild swans comes back to me whenever I think of the place. My diary records that on one occasion we had a young native companion, "roast, with forcemeat," for dinner, and that it was "delicious." Also that, two days later, we experimented upon a swan, and found it "not so good." The gun, of course, went out for duck and snipe and quail in their season, to vary the too-constant mutton. They were not easy to get, for this is no true game country, for those huge sheep stations, with their lonely dams, were practically wild country for them.

In the elbow of the river at the corner of our paddock we used to watch for the platypus, which had a home there, under the broken banks. Four of these precious rarities were shot in the six years - we are sorry for that now, but were proud of it at the time - and the house smelt horrible while their dense, oily coats were being stripped off and dressed. The same river provided a beautiful set of furs for my friend at M_____; they were made of the golden brown skins of water-rats, caught and cured for her by her butler. There, too, we used to sit amid the evening mosquitoes, and angle for blackfish and "yabbies". It was a corner much beloved by the school-boys of our acquaintance with Saturday afternoons or long twilights upon their hands. One young fellow, the son of a lawyer in the town, spent many patient hours there, all alone; but we, prolonging his enjoyment by the offer of a meal or a bed, would sometimes look on at his tranquil sport, amused by his methods. When he needed to bait a hook, he bent the crown of his head earthward and took off his cap gingerly, afterwards combing his rough locks with his grubby paw. He kept his worms there, between his cap lining and his hair; it saved the trouble of a bait-can. When he caught a fish, he slipped it into his pocket, where it tangled itself with his handkerchief and oddments in its dying throes. We were somewhat nicer in our proceedings. Neat little blobs of meat at the end of strings were let down into the water, and when the tiny cray-fish fastened upon them they were lifted delicately into the air, the whole art consisting in not frightening them into dropping off until the bank was under them. Nothing messy or murderous or offensive to the sensibilities of women and children - until the black creatures were boiled red for tea or breakfast, and that was done by the cook in private, and we tried not to know anything about it. A few dozens of them, warm from the pot, with bread and butter, made a delicious meal.

But Nature took toll of us in return for what she gave. Eagle-hawks, that hankered after the lambs, and their lesser brethren that were interested in the poultry, hares that loved young vegetables with the morning dew upon them, nocturnal wild-cats, and the tame cats gone wild that were far worse than they - for them, too, the gun was kept in readiness, and, alas! I grieve to say, the trap... Ada CAMBRIDGE writes on bushfires in the area of the "Parsonage on the Wannon" from 1877-1884.

Why does the Australian pastoralist provide free board and lodging for every loafer that comes for them, instead of kicking him out and telling him to go to work? Because he knows how easily and safely the loafer could avenge himself if sent empty away - and how well the loafer knows that he knows it. There is a tacit understanding between them. The wise blackmailer is easy in his demands - the regulation allowance and no more - and the blackmailed is glad to purchase valuable good-will at no greater cost. It is one of the oldest institutions of the country, which even we upon our hundred acres would not have dared to flout. Our wealthy but frugal neighbour did, as we were told, and reaped the consequences - which would not have mattered much if the undeserving poor had not stood in the path of the reaper. Thus, for weeks together, G. and his man never put up their horses at night until they had circled round and round the place, looking for little trails of dead sticks and straw carefully led into a fat paddock that was not ours, as a fuse to a mine. One Sunday night, on the way home from church, without looking for them - because they were all alight, though refusing to burn effectively without a wind - he found three.

This was in what we call the "fire year". That summer we had ten in almost ten consecutive days, each of which menaced the mass of old sun-dried woodwork in which we lived. Two horses stood ready to mount at the first signal, every homestead around being similarly prepared. We slept with blinds up and windows open, and anyone waking would at once jump up and go out and look into the night for the dreaded flare. No matter where it was, or when, the men were off to it with the speed of professional firemen; and if it was near, or the wind towards us, we women started to make bucketsful of tea to send out to them. Helpless with a new-born baby, I used to lie and smell the smoke and listen to the flap of the bags, and wonder what was happening, and nearly died from want of rest. One morning one of us unluckily remarked that "actually here was breakfast nearly over, and no fire!" Scarcely were the words uttered before the groom appeared with his "Fire, sir!" and the next instant both were galloping across the downs, to join other horsemen converging from all points of the compass upon the same spot. It was Saturday morning, and that battle lasted until Sunday, when we could have walked, we were told, ten miles in a straight line from our back door without going off burnt ground. One other morning, when I was well enough for a drive and wanted to do some shopping, and it seemed safe to leave home for an hour or two, G. Took me to the township. We were hurrying through our business in the street when a man came up and said to G., "There's a fire over your way, sir." We had a pair of very fast horses, and we flew down those hills in record time. Reaching home, we found our good neighbours pouring water over the charred posts of the garden fence.

Of course, this was not all incendiarism. Even the aggrieved sundowner is not so bad as that. Under suitable conditions, nothing is easier than to start a blaze that flies out of your hand before you see the spark. A castaway bottle, a little ash knocked out of a pipe, will do it. My own eyes have proved to me from what a small cause a great conflagration may result. A cavalcade of vehicles from M_____, while we were staying there, was on the road to church; it was a well-used fenced Bush road, all dust and wild peppermint weed - a fire-break in itself, one would have thought. But I, in the second buggy, saw a flicker under the wheel of the first; it ran from one scrap of tinder to another and was away over the country before one could draw breath. "Like wild-fire" is the best image for speed that I know. It used to pour over those grassy rises just as released water does, a spreading black stream with a scintillating yellow edge; not a menace to life as in forest country, but sickening to the heart of one who knows his home is to windward of it, and knows the frailty of the most carefully-prepared "break". The buggies were stopped, the men in their Sunday coats out and after it in an instant, but there was no church that day for any male of the party except the parson. An examination of the spot where the fire started showed that the buggy wheel had passed over a wax match. The unwritten law of the Bush is that no matches must come into it, at these times, except the wooden ones guaranteed to strike on the box only.

The "fire-year" - or fire summer rather (1879-80) - is literally burnt into my memory. Now, when I smell Bush smoke I feel as I would at the sudden sight of blood in large quantities. All those old scenes come back, and the old terror of the nerves, which were strained so long that the effect upon me was something like what in pre-scientific days was called going into a decline. My strength refused to to return after the birth of the child that arrived in the middle of the ordeal, so that at last I had to be sent away out of sight, sound, and smell of the place, to give me a chance to recover. But the worst was over before I went. We were sitting at tea one night - evening dinners, by the way, had early been given up - when there suddenly fell upon our ears the sound of rain pattering. We nearly jumped from our chairs; we looked at each other, beyond speech; and then I burst into a fit of hysterical tears - some of the happiest I have ever shed.

In the evening, a neighbour rode over - for the first time, as he remarked, without his sack on the saddle, and for the first time on any errand unconnected with with its use. We had all been keeping guard of our homes for weeks that had seemed years, friends meeting only on the field of battle - as heroic a field of battle as those that our "contingenters" went to, and better than the playing-fields of Eton as a preparation for them; but we were free at last. And we could hardly realise it. All the evening we sat, almost in silence, inanely smirking at each other and listening to the rain. It was too sweet a sound to drown with talk.

The "old parsonage" was (allowing again for the enchantment that distance lends) a charming home; but it had that against it. I have been glad ever since to live where there is nothing more to do than turn the gas off at the meter when one goes to bed... Ada CAMBRIDGE, Poet, Author: some external links:

Sources:

"Thomas Francis Cusack RUSSELL was a far travelling Anglican priest. In 1850 he was appointed vicar at the Wannon, with his first parsonage in Coleraine, which was at the centre of a widespread parish. He was the first, and for a long time, the only parson, of any denomination in the far inland of Victoria. He was a learned, witty man, vastly popular with all men in his district. He could have had any living in Bishop PERRY's gifting, but was content with his simple life at Coleraine, where he served as churchman for twenty-six years"

...in the matter of the next appointment, it fell to our lot to be promoted to what I think was considered at the time the most important country parish in the diocese.

...That fifth home was a survival of the old, old times - quite the beginnings of the colony. In those old times, before townships were, the princely pioneer squatters (our late host the chief), wishing to have their church represented amongst them, made a first gift for the purpose of one hundred acres of their fat lands and a house - the nucleus of this house. It was an inalienable endowment, not to any parish - for there was none - but to the incumbent for the time being; so that afterwards, when it came to belong to a parish, whose centre of town and church were six miles off, the vestry could not turn it into money, as they desired, so as to bring their parson to headquarters.

I am glad it was he - not his predecessor...

...we were often in straits owing to our six miles' distance from them [stores, schools, church, doctor, next-door neighbours]. Between us and the road lay a (to us) bridgeless river - it is called a river - which it was necessary to pass to get to church and back, and at the best of times its banks at the crossing-place were so steep down and up again that I dreaded the spot on a dark night, after going through it in safety hundreds of times, and after all the breaking-in of such things that I had had. Its flood-water used to overflow into what we called our "lane", the unavoidable approach to the house, covering the fences on either side in the lower parts, which between-whiles were either soft bogs or rough ruts and ridges like those of a frosted ploughed field. Owing to these lions in the path we had few visitors in winter. In summer there were Bush fires - of which I will say more presently...

...Then there were the long waits for the doctor in dire emergencies, and per-mile fees (if the doctor were non-Church-of-England, or you could successfully save yourself from taking charity) for his tardy attendance. Our groom nearly killed a pair of horses one night - when a commonplace domestic event was impending - trying to make them do twelve miles in time that would but comfortably cover four. One day my nurse and I found a white speck on the throat of the youngest baby, when no man or buggy or even wood-cart was at home. While I looked at my devoted colleague in despair she began briskly to gather and tie on our respective hats. "We have to get him to the doctor somehow," said she. And off we started, and carried him (he was then twenty-one months old), turn and turn about, the whole six miles, all up-hill, since there was practically no alternative. As it chanced the doctor, when we got to him - dead beat as ever women were - laughed at the baby's throat; but the incident illustrates some of the drawbacks of our isolated life which were not suffered by our successors...

...Household supplies had to be laid in wholesale - sacks of sugar and flour, chests of tea, boxes of kerosene and candles. We had to make our own bread, and our own yeast for it; we had to kill our own mutton and dress it up; gather our own firewood and chop it. This meant keeping a man (for the first time); beside whom we had a general servant, a nurse, and a young lady companion.

...

A new member was added to the household in a singular manner. The selectors with families needed a school. To get a school, Government had to be assured that so many children - twenty-five or thereabouts - were entitled to it; and the parents came to ask if we would aid them to make up the number. Our three were babies, and we certainly did not mean to foist them on the State for their education, but we somehow reconciled it with our consciences to sign the requisition form on our poorer neighbours behalf. Thus they got their school - a tiny white wooden building, and one teacher. The building, consisting of a schoolroom and teacher's quarters, was set up on the public highway, just outside our outer gate, on the bank of the so-called river (where the bridge was), a night camping place of all the teamsters and drovers on the road; and the teacher appointed to live there, beyond call of any other house, was a good-looking young woman.

...

Besides the milking cows of the establishment, we always had a herd of bullocks on the place. We bought them as "store", intending to sell them as "fats" - intending, indeed to make our fortunes as land-owners and cattle-dealers. Our hundred acres were notoriously one of the rich patches of the district, coveted by our wealthy neighbours as badly as ever Ahab coveted Naboth's vineyard; anything could be made of it - on paper.

...

We were very close to nature at this place. The wild things lived with us even more intimately than at Como. Opossums did not keep to the river; they loved the fruity old garden, and stuck to it in spite of dogs and guns. Driving home o'nights we used to see them sitting on the house roofs, silhouetted against the sky, and they used to keep us awake with their talk to each other in a tree near our bedroom window. On one occasion we were roused by the nurse calling to us that a 'possum had come down the chimney, and was flying round the nursery and smashing everything. A candle and a stick soon ended the career of that enterprising little animal.

...

But the terror of terrors was - fire. The land was rich, the years were droughty, and we the innocent victims of a systematic incendiarism directed against somebody else. The somebody else was like the Russian Government, all palace and diamonds at the top and all black bread and taxes at the bottom; or like the Government that we here groan under, which acts upon the theory that the more you cut down trade the more money you will get out of it. A station that "marched" with our Naboth's vineyard had a black mark against it.